Sandy Trand (Mentor: Prof. Domínguez)

During the summer of 2020, I conducted research and populated the Omeka-based Teach with Music and Film database.

Abstract/Purpose

The purpose of the database is to compile music and film from around the world that may be used pedagogically. During the summer, I added new entries to the existing database and conducted research using popular & scholarly sources. All of this was done in preparation to launch the website and promote it to other professionals within the academic discipline of history. Both Professor Domínguez and I hope that this tool will be helpful to both students and faculty.

Background

This project began as an extension of a 2014 article published in the journal Teaching History entitled, “Using Music to Teach Latin American (and World) History” written by Daisy Domínguez, reference librarian, and history professor. In it, she argues for an expanded usage of music as a teaching tool and the development of a music suggestion database with information on artists, genres, and contextualization of the song references. This led to the development of the Teach with Music and Film database.

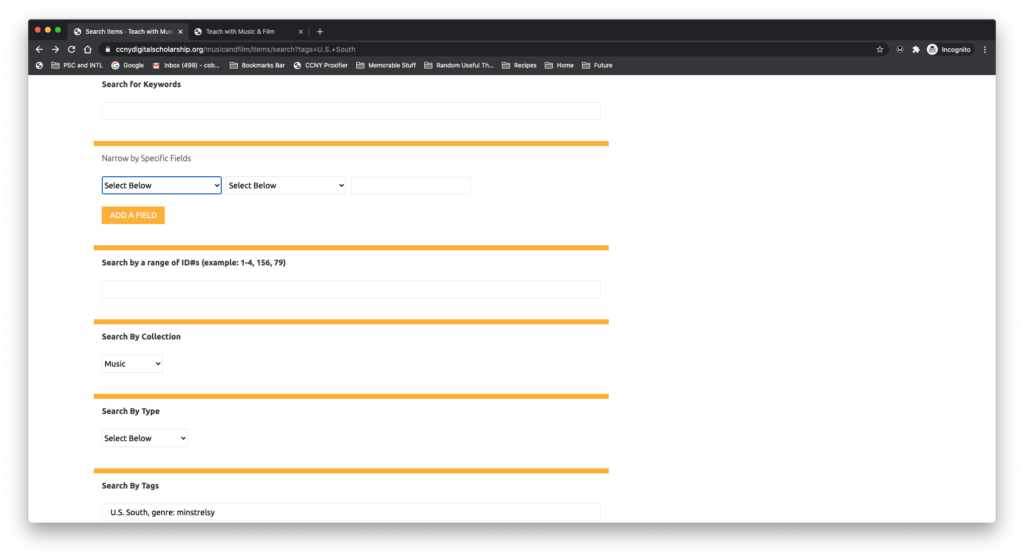

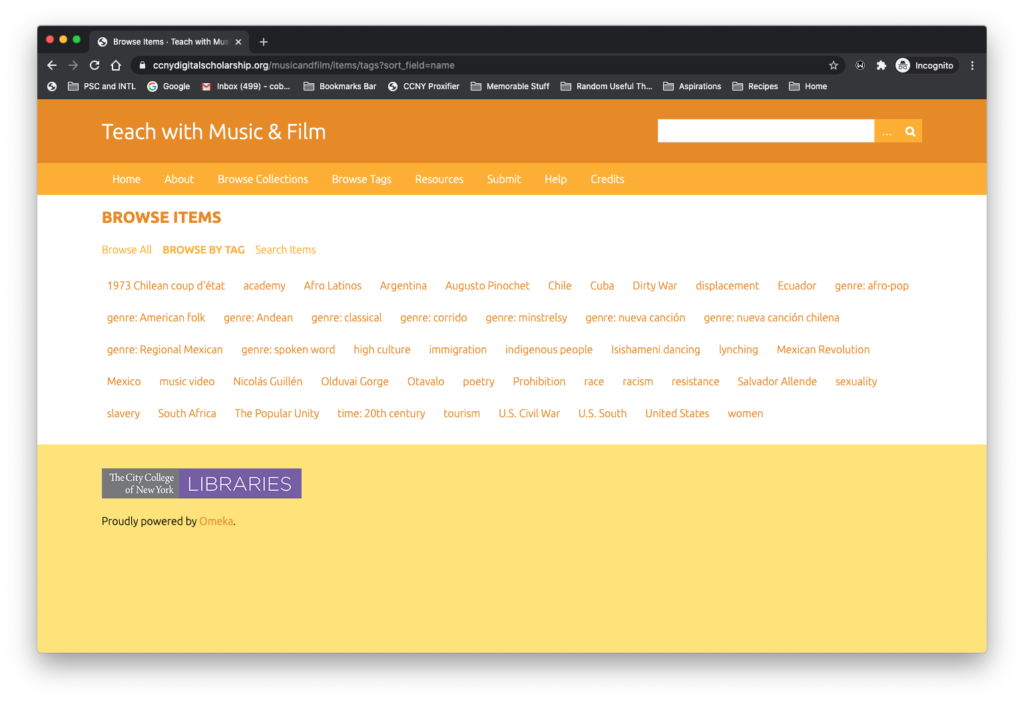

Several elements differentiate this database from existing ones. Currently, there is a database entitled Teach with Movies which covers only films. While the breadth of topics the movies they cover are far more broad-reaching beyond politics, history, and into disciplines such as science, the Teach with Music & Film database serves a different purpose. Teach with Movies targets secondary school educators and parents who home-school and they cater to their audience through the provision of materials such as teaching plans. Teach with Music & Film aims to merely serve as a jumping-off point in helping either a secondary or higher-level educator enhance a lesson by incorporating an audio-visual aid and for college or high school students to conduct research. This is done so with the inclusion of a reference citation to either an academic publication or periodical for the majority of entries. Additionally, there is a greater emphasis placed on the ability to modify one’s search. By utilizing the Omeka platform, one can locate material using a variety of search terms ranging from subject matter to genre without resorting just to a browse list. Moreover, there is little overlap in collections. The Teach with Music & Film database contains more foreign titles and niche films especially those with smaller releases.

Teaching with Music & Films is also distinct from existing databases as often those are devoted to a single genre or topic. For instance, the Roud Folk Song Index is devoted to English-language songs published mostly before 1900 with a special emphasis placed on folk songs and broadside ballads. There are also those devoted to a specific topic as is the case with the Cantos Cautivos (Captive Songs) digital platform which focused on the songs associated with those living under the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

Methodology

- Acquiring context

- We agreed on specific eras or movements early in the summer. It was important to finalize those topics since preliminary research about the topic was required. The topics chosen were the Nueva cancíon movement, apartheid-era South Africa, and the U.S. South which was based on a preexisting list supplied by Dr. Adrienne Petty, former professor of History at City College who contributed a list of songs and song descriptions compiled by her students for an assignment. While the focus was chosen based on our familiarity and/or interest with the subject, I needed to read information about the periods to fully understand the context and conditions in which the materials would be produced. Oftentimes, the process began with reading various secondary sources whether it be books published by academics or periodicals. Ebooks and reference materials were accessed through existing ebook collections such as ProQuest Ebook Central or the Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- Scouting materials:

- Reading popular and scholarly literature to find songs and films had a dual purpose. Generally, these sources were pulled from larger, more general databases such as OneSearch or LexisNexis or very often, popular periodicals such as the New York Times or The Guardian. These were a way to both familiarize myself with the politics of the creative process and find possible material to develop into entries. More often than not, the authors made mentions of songs and films with political messaging or those that were historically significant. If needed, research was conducted within subject-specific academic journals to ensure that an informative description and possible references could be had for each of the entries.

- Some of the other resources I used in acquiring materials for future entries include indices, discographies, and filmographies.

- In addition, public forums such as IMDb for films, Discogs for music, and foreign news agencies/publications were instrumental to the discovery of new materials. They were most helpful in locating more niche films, those appearing in mainstream streaming services such as Netflix or Hulu, and those that didn’t have a wide release in the English-speaking world or a wide release, in general. IMDb and Discogs also provided a wealth of information about the resources such as the languages it featured and alternative names it may have been released under. Most of the foreign publications used, which excluded English-language periodicals based in either the U.S. or the U.K., were accessible through LexisNexis. Moreover, all of the resources used in the research of the material or the references cited on the entry’s page were in English. Despite the shortcomings associated with the aforementioned practice, it was important for me to counter as much as possible the biases present within the production of scholarly research and the prioritizing of lingua franca languages most notably, that of English.

- Creating a catalog

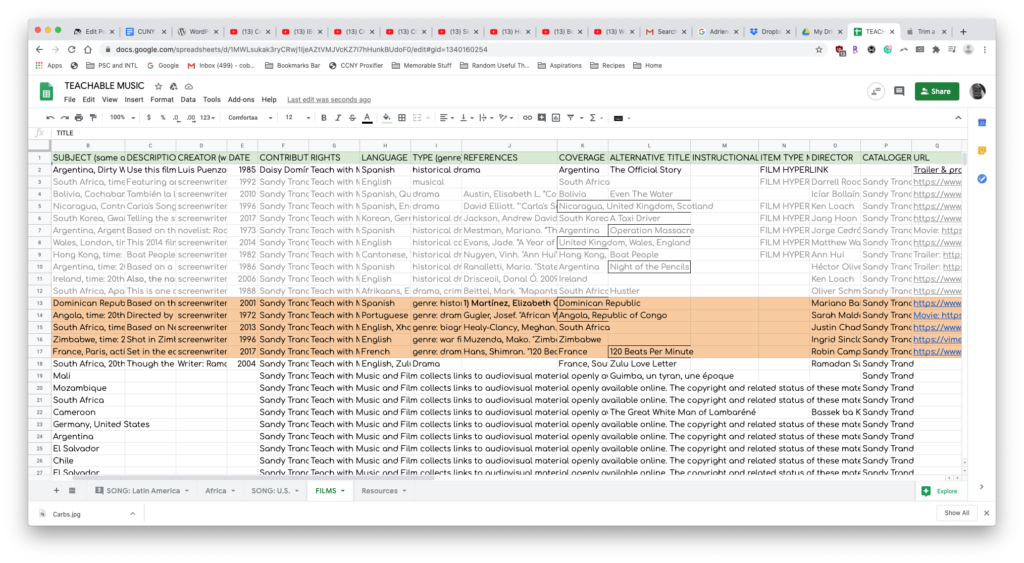

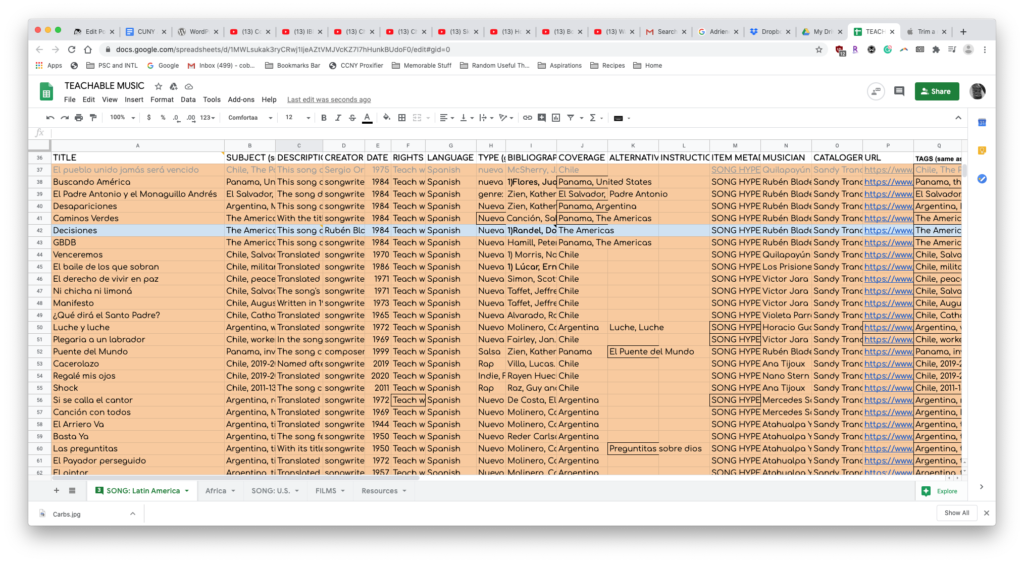

- In preparation for populating the database, a catalog was created in the form of a spreadsheet on Google Sheets which facilitated easy collaboration. Within the spreadsheet, columns categorize the metadata that would be entered into the database so that I could easily find them when I needed to make entries into Omeka. Some of the categories include:

- coverage In what country was this created? Or, what country features prominently?

- creator For music, it was the songwriter or composer and for films, it was the screenwriter

- alternative title Often, the non-English language materials were sometimes promoted in the English-language markets using a title that wasn’t the direct translation of the original name. Frequently, the original title is in another language and the alternative title is in English. It was part of our initiative to ensure that we weren’t going to prioritize English-language audiovisuals.

- references Links to both scholarly and popular literature where people go to find more information about the material

- In preparation for populating the database, a catalog was created in the form of a spreadsheet on Google Sheets which facilitated easy collaboration. Within the spreadsheet, columns categorize the metadata that would be entered into the database so that I could easily find them when I needed to make entries into Omeka. Some of the categories include:

- Synthesizing the information

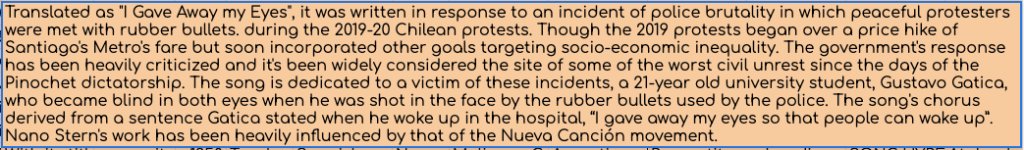

- Found within every entry on the database, is a description with a brief explanation of the song/film’s plot, how it can be used pedagogically, and any relevant information that the cataloger has deemed necessary to the full understanding of the material.

- Imputing the material’s metadata into the Omeka-platform

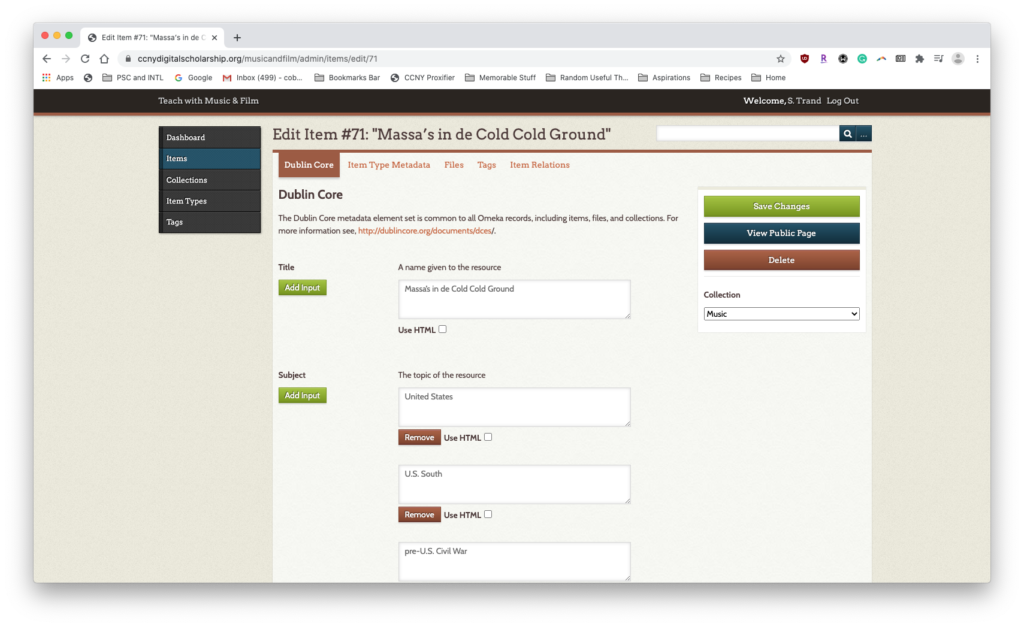

- The metadata categories on the spreadsheet correspond to an existing category on the Omeka-based platform. The categories on the database were based on the metadata standard, the Dublin Core. Moreover, a publicly available link to either the film’s trailer or the song was acquired and incorporated into the entry. Some of the sites utilized include Youtube, Vimeo, and the collections at the Library of Congress.

Spreadsheet for Films

Spreadsheet for Latin American & Caribbean Songs

Description for the song “Regalé mis ojos”

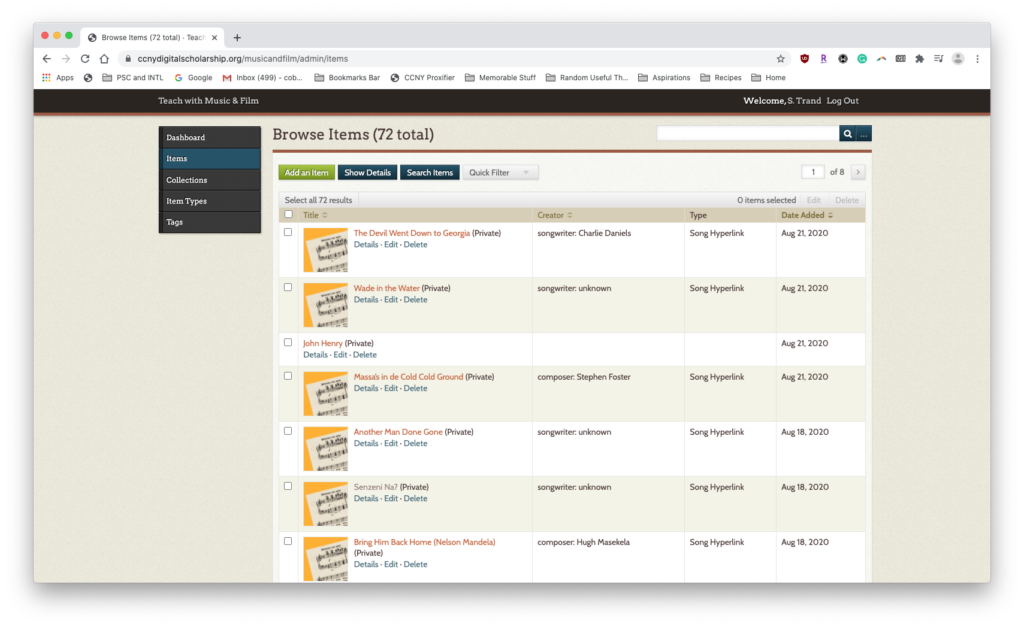

The backend of the database

The process of entering the descriptive metadata

The Database

Omeka is an open-source web-publishing platform that is primarily used in the display of digital collections and exhibitions. The Teach with Music & Films database is a digital collection of songs and films with a pedagogical purpose and uses the Omeka Classic Platform. Originally developed by Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, it’s a practical platform that is more conducive to those in high school or university performing research since it has functions such as the ability to conduct boolean searches.

Skills Learned

Whilst working alongside Professor Domínguez, I was able to hone existing skills as well as acquire new ones. During the summer, I gained experience working with metadata. Specifically, I learned about one of the metadata standards, Dublin Core, a classification system that has been a popular force in the movement to standardize digital collections. I was also able to familiarize myself with the terminology associated with metadata. Much of the summer was spent learning about descriptive metadata which focused on the information used to classify and describe the two key collections, film and music. My descriptive metadata duties included differentiating between versions of resources and creating descriptions for each of the references.

In addition to gaining experience working with metadata, a key component of my duties required me to expand upon my research skills by conducting research on a broad range of topics. Despite an initial selection of a few topics, any material that was unearthed and deemed a potential reference was added to the spreadsheet. As stated earlier, a focus on helping students and finding audiovisual aids to suit their research and/or pedagogical use is our main objective, as opposed to a focus on a particular topic. Research was required for both the context of the period the material referenced or the period in which it was created and for the entries themselves. We made an effort to focus on films by and about people who were not Americans. Over time, one process I learned was that of standardizing the research process. I learned about the merits of using specific databases and/or indexes. For instance, all searches began broadly with initial searches for information about the material on larger platforms such as JSTOR and OneSearch. From there, I went on to focus on subject-specific journals such as Popular Music or African Studies. However, for materials in which there was limited English-language scholarship, I needed to steer away from academic publications to that of popular literature, most notably that of international news publications through the LexisNexis databases. Oftentimes, information was more readily found in the English language editions of foreign press agencies and/or newspapers. For some topics, most notably that of the Nueva cancíon musicians, specialized resources such as the Hispanic American Periodicals Index were utilized in addition to the aforementioned strategies.

Finally, I also acquired writing and, crucially, editing skills. In addition to gaining experience editing by writing the descriptions produced for each of the entries, I also learned to be more judicious in choosing tags and subject matter. The platform has some search limitations. Omeka presented itself as a challenge to be concise and yet not to generalize the entry, rendering it difficult to find. Careful discretion was also exercised on both our parts in reducing the number of tags so that the tag page would not be repetitive.

Conclusions/Findings

During the summer, the number of entries has grown from 10 to a total of 94. The project’s next steps are to reach out to history faculty at various schools across the nation to both create awareness about the project and to grow the number of entries. Through outreach, the platform will become increasingly diverse. The final goal of the project is to create a topically-diverse database of films and music with a pedagogical purpose.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank those on the ORCA for the opportunity, funding, and guidance. I would also like to express gratitude towards electronic resources librarian Sean O’Heir and Adriene Lara of the Digital Scholarship Services division for their technical assistance. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family for supporting me throughout the summer.